Reshoring American Manufacturing: Why It May Not Be Possible—or Even Desirable

The Trump administration is laser-focused on bringing back American manufacturing, but numerous roadblocks stand in the way

Jobs and factories “will come roaring back,” President Trump said following his April announcement to impose “retaliatory tariffs” on over fifty countries—the latest effort by the administration to revitalize US manufacturing. To underscore the effort, the White House actually maintains a running list of reshoring commitments by businesses.

Yet, aside from CEOs’—sometimes dubious—pledges to bring manufacturing back stateside, progress on reshoring has been lackluster. The Kearny Reshore Index fell by over 300 basis points (and into negative territory) from 2023 to 2024. Another study found that even as 81 percent of CEOs and COOs plan to bring their supply chains closer to home, only 2 percent had fully completed their reshoring or near-shoring plans. That tracks with forecasts by investment banks and rating agencies, which find that investment and economic growth in the United States have not changed despite recent headline-grabbing investment pledges by the private sector.

The efforts to reshore US manufacturing stem from noble goals: a desire to improve America’s competitiveness and national security and drive up blue-collar wages and employment. Making it a reality, however, is another question altogether. In what follows, we discuss challenges to reshoring and why government relocalization policies may not be desirable. We close by making recommendations for policymakers and manufacturing leaders moving forward.

Key Obstacles to Reshoring US Manufacturing

Roadblocks to the US reshoring movement include:

Policy uncertainty.

Companies feel uncertain about everything: the incidence and size of import tariffs, high interest rates, other countries’ retaliatory acts against US trade protectionism, the livelihood of Inflation Reduction Act and CHIPS Act subsidies, and future procurement by US agencies. Frequent policy whiplash only deepens this uncertainty, not to mention fears that current regulation may be swiftly undone when the next administration enters office.

Such volatility is toxic for large investment decisions, like the development of new manufacturing plants. Facilities can take years to build and often cost multiples of average gross operating surplus, particularly in basic manufacturing industries. And these costs are rising: the majority of respondents to a recent CNBC survey estimated that the price tag of building a new domestic supply chain would be around double or more than current costs.

As a recent FT opinion piece put it, “Rational boardrooms will not risk years of profit by breaking ground on new facilities if tariff rates shift again and render investment less competitive.”

Nagging supply and demand issues.

The true problems with reshoring are inherently structural and thus cannot easily be willed away.

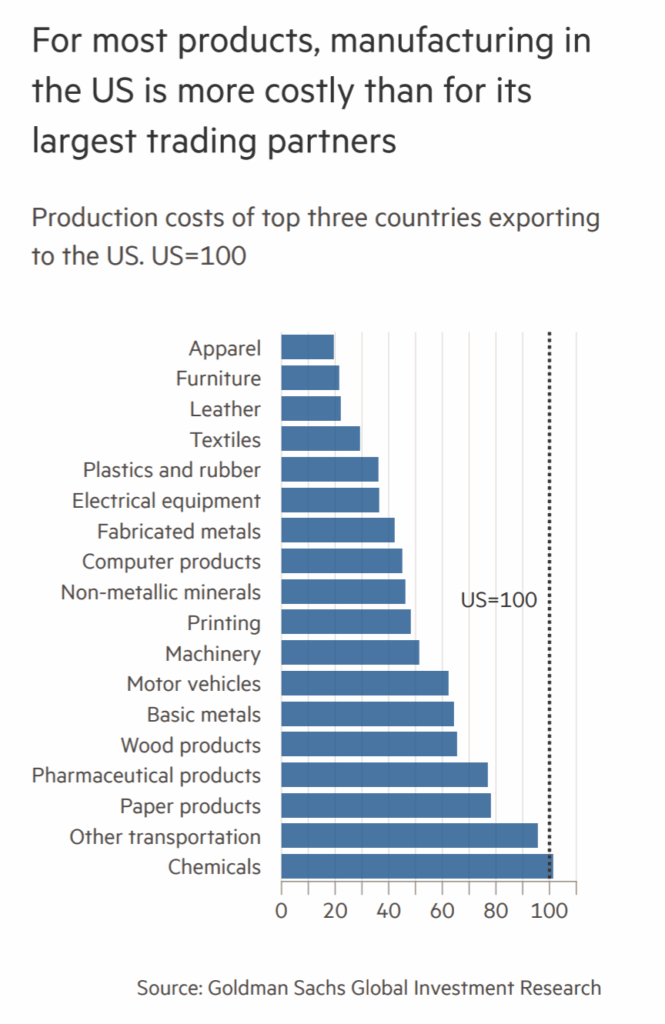

On the supply side, labor availability and skill gaps in the US are a top challenge—particularly in manufacturing. Apple CEO Tim Cook summarized this when he said that companies go to China “because of the skill, and the quantity of the skill in one location … In the US, you could have a meeting of tooling engineers, and I’m not sure we could fill the room.” Add to that high production costs, including setup costs and variable (running) costs, such as raw materials, energy, utilities, logistics and freight, and third-party services.

On the demand side, consumer confidence and spending will continue to wane, particularly as reciprocal tariffs begin to take effect. While consumer confidence rose in May for the first time in five months, there is still a 40 percent chance of a recession, according to JP Morgan.

Evidently, the supply and demand issues of the kind described do not make reshoring any more attractive or likely in the eyes of multinationals.

A lack of capital.

Moody’s recent downgrade of US debt means higher borrowing costs. These will almost certainly trickle down to the private sector, resulting in higher effective interest rates and impediments to taking credit or issuing bonds to finance reshoring.

Yet investments in reshoring are undertaken not only by domestic companies, but in the form of foreign direct investment (FDI). For years, the US has been the largest recipient of FDI—but FDI into the US has been shrinking and is expected to decline even further as imports dry up and exporting countries have fewer US dollars to invest back into the US. To make matters worse, the latest draft of the “One, Big, Beautiful Bill” authorizes the Treasury Secretary to impose retaliatory taxes on inbound investment originating from countries that make up more than 80 percent of US inbound FDI stock. Clearly, the threat and possible use of taxes on inbound investment dampens the willingness of foreign companies to inject capital into reshoring projects.

Reshoring requires bringing back entire value chains.

A country that is serious about reshoring needs to reshore entire value chains for reshoring to work. Otherwise, the problems of allegedly risky supply chains and dependency on hostile powers are simply pushed down one rung in the production chain.

In 2024, however, only 5 percent of manufacturing executives affirmed that they sourced all their raw materials locally, while just 28 percent said the same of semifinished products. Take the semiconductor industry: According to industry experts, there are scant US-headquartered suppliers for core upstream semiconductor products (highly purified elements, chemicals, specialty gases, etc.) and no dominant US players in the crucial downstream assembly, testing, and packaging industries. Similarly, the battery industry relies on a number of critical minerals, none of which are mined in the US in sufficient quantities.

Meanwhile, the current administration’s across-the-board tariffs on Chinese, Southeast Asian, and European products make sourcing intermediate products like steel and aluminum—and thus the entire production of finished products—more expensive for companies otherwise willing to reshore. That very dynamic played out in the US just a few years ago: research on Trump’s 2018 tariffs revealed that domestic manufacturers largely lost out by paying more for raw materials.

Past failures loom large.

In light of the above, it may not come as a surprise that many reshoring projects fail. A 2025 OECD report finds that reshoring produced domestic dependencies and bottlenecks that made countries no more resilient to external economic shocks—in fact, supply chain localization made half of the assessed economies more vulnerable. It stands to reason that well-informed and forward-thinking multinationals will be aware of the considerable likelihood of failure and a priori be unwilling to reshore.

Reshoring by Fiat: A Thought Experiment

As stated above, US companies are increasingly driven to reshore. So let’s engage in a thought experiment: What if the US government ordered reshoring by fiat?

First, this would not lead to an unmitigated victory for the US. After all, if a country attempts to produce everything on its own, it will end up doing nothing particularly well. It’s like Adam Smith’s adage: focus on what you’re good at and trade for the rest.

Second, reshoring by fiat would draw away scarce resources from those industries in which the US has an international competitive advantage (i.e., lower costs or superior quality), which allows them to export. Examples include professional services, pharmaceutical products, agricultural goods, or large civil aircraft. If forced to compete with reshored manufacturers, these now highly competitive industries will face higher relative costs—for employees, capital, and raw and intermediate materials—while their export markets would likely be forestalled by tariff retaliation.

Third, to make reshoring worthwhile and overcome thirty years of lost competitive advantage in manufacturing, the benefits for companies must outweigh the costs in the medium to long terms. Reshored companies currently have three major avenues (or indeed, a combination thereof) available to them:

- Improve manufacturing productivity through automation and reduce labor content as a proportion of overall costs (according to CNBC, 81 percent of businesses would use automation more than human workers if manufacturing comes back to the US)

- Increase prices and reduce product variability

- Invest in innovative process technologies that are more efficient, have lower-scale requirements, use fewer energy-intensive inputs, and/or produce less waste; ideally, then, the products are imbued with so much innovation that manufacturing costs don’t matter (e.g., biologics or semiconductor manufacturing)

The downsides of the first two strategies are evident: fewer jobs for humans and higher costs for consumers. The problem with the third is that such a strategy cannot be implemented in every manufacturing sector, from paper and plastics to precision machinery and everything in between. It is also extremely capital-intensive and unlikely to occur if the domestic market is artificially protected by measures isolating US producers from international competitors, know-how and intellectual property, capital, and—increasingly—scientists and researchers.

Thus, even a successful reshoring effort would probably be undesirable for the US.

Three Reshoring Recommendations for Policymakers and Executives

An across-the-board reshoring of manufacturing into the US is unlikely to succeed. But that doesn’t mean there aren’t sensible ways to pursue some reshoring to improve supply chain resilience. Here are three recommendations:

-

- Be strategic. Reshoring can be truly successful only in a few select industries. Policymakers should think about where to incentivize it. Sectors with high national security risks and ripe for innovative disruption are logical places to start.

- Supplement reshoring with industrial policy. Well-executed reshoring efforts must be actively incentivized. Research has shown that a broad definition of industrial policy is particularly successful in this respect, encompassing investments in infrastructure, education and upskilling, technology adoption, and more flexible workforce models.

- Friendshore. As noted, no country—the US included—can manufacture everything by itself. Sourcing from friendly countries, developed and developing alike, can offer strategic value chains and create a resilient supply chain ecosystem.

Job losses from outsourcing and offshoring, risks to national security, and de-risking global value chains are serious issues—and attempting to solve these via reshoring is a virtuous endeavor. However, current regulatory, economic, and structural challenges make achieving this goal unlikely, particularly if reshoring were to be decreed by the government.

Business leaders and policymakers would do well to take more strategic, deliberate, and focused approaches to revitalizing US manufacturing and ensuring supply chain resiliency.